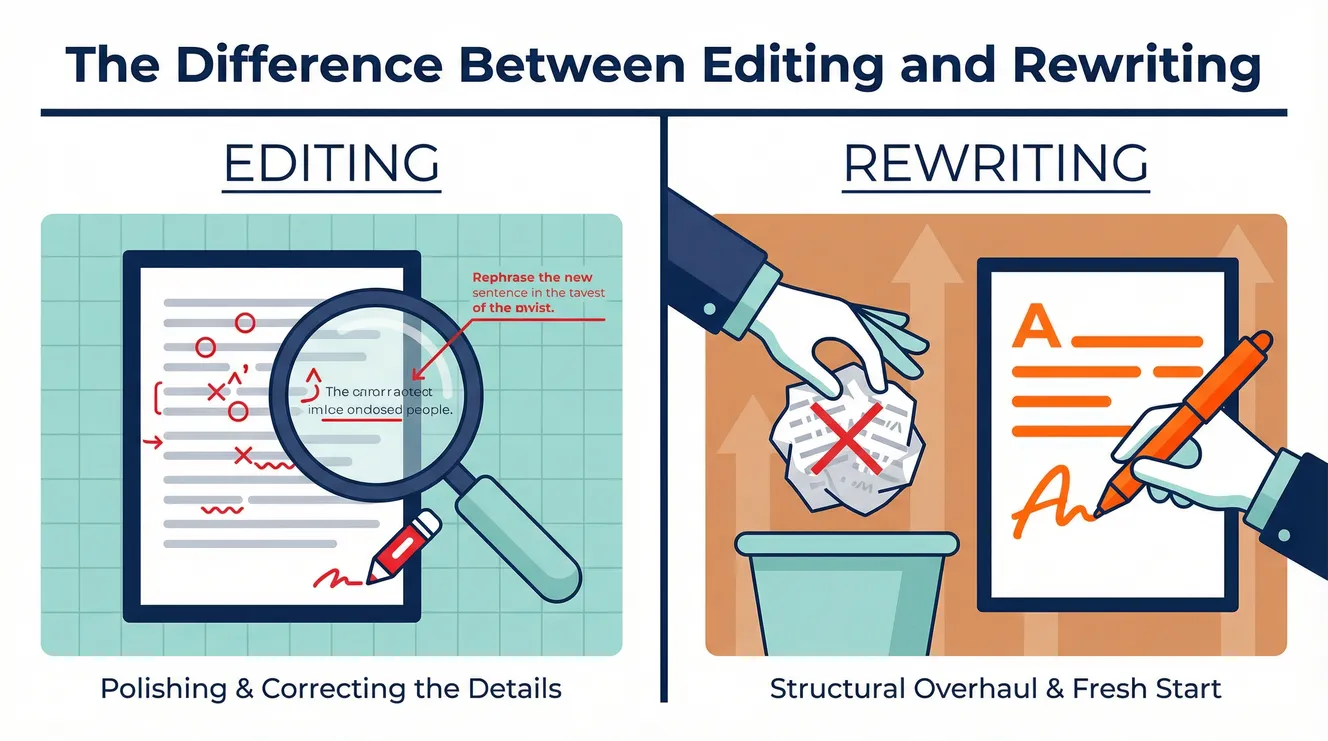

Editing and rewriting occupy opposite ends of the revision spectrum, yet writers constantly confuse them, leading to wasted effort and frustrated manuscripts. Editing works with existing material—tightening prose, clarifying sentences, adjusting word choices. Rewriting creates new material, reimagining scenes, restructuring arguments, reconceiving characters. The former is refinement; the latter is re-creation. Understanding which tool to wield, and when, separates professional writers from amateurs who either polish flawed foundations or demolish sturdy structures unnecessarily.

The confusion is understandable. Both processes involve revising text, both improve quality, and both feel like “fixing” your work. But Writers Digest editorial guidelines make a critical distinction: editing works within the boundaries of your existing draft; rewriting questions whether those boundaries should exist at all. A line-edit might transform “He walked slowly” to “He ambled,” but a rewrite questions whether this scene should feature walking at all, or if the character should be someone else entirely, or if this entire plot thread serves the story.

The Core Distinction: Working Within vs. Working Without

The fundamental difference between editing and rewriting lies in your relationship to the existing draft. Editing assumes the draft’s foundation is solid—you’re improving execution, not concept. Rewriting assumes the concept itself needs re-examination. This isn’t about degree of change; it’s about nature of change. You can edit 90% of sentences and still be editing. You can rewrite one paragraph and be rewriting.

Think of it as the difference between renovating a kitchen and redesigning a house. Renovation (editing) keeps the walls, plumbing, and layout but updates cabinets, countertops, and fixtures. Redesign (rewriting) asks: “Should this kitchen be here at all? What if we removed this wall? What if the sink belonged in a different room?” The Creative Penn’s self-editing framework emphasizes that rewriting requires a different mental frame: you must be willing to delete entire chapters, merge characters, reverse arguments, and question every assumption your draft makes.

The Decision Tree: Edit or Rewrite?

Edit if: The structure serves the purpose, characters/plots are coherent, argument is logical

Rewrite if: Structure feels forced, elements contradict each other, readers can’t follow the logic

The Metaphor of the House

Imagine your manuscript as a house. Editing is interior design—painting walls, rearranging furniture, hanging art. Rewriting is architecture—moving walls, adding rooms, changing the foundation. Both improve the house, but they solve different problems. If the living room feels cramped, you can edit by removing furniture or rewrite by knocking down a wall. The former works within constraints; the latter removes constraints.

The tragedy is that most writers apply interior design to houses with cracked foundations. They spend weeks perfecting sentences in scenes that shouldn’t exist, polishing prose in chapters that need demolition. Conversely, some writers sledgehammer walls that only needed paint, rewriting entire sections that could have been saved with careful editing. Professional editors report that 60% of manuscripts they receive have the wrong revision approach applied, wasting months of writer effort.

When to Edit: The Green Flags of Revision-Ready Drafts

Knowing when to edit is as important as knowing how. A draft ready for editing shows specific signs of structural health. Rushing to edit before these signs appear is like varnishing furniture before the glue dries—you’ll trap problems beneath a polished surface that will eventually crack.

Structural Coherence

Your draft is edit-ready when the architecture holds weight. In fiction: characters act consistently, plot points follow logically, scenes serve a clear purpose. In nonfiction: arguments build sequentially, evidence supports claims, transitions connect ideas. Now Novel’s revision guide suggests the “airplane test”: can you explain your structure to someone in 30 seconds at 30,000 feet? If yes, you’re ready to edit. If you find yourself saying “This part doesn’t quite fit but I can fix it,” you’re not editing—you’re rationalizing a rewrite need.

Emotional Truth

Edit-ready drafts feel emotionally true, even if the prose is clunky. Readers can sense when characters act from genuine motivation, when arguments stem from real conviction. If you’re defending character choices to yourself (“She’d be angry here because…”), the emotion isn’t yet on the page. Poets & Writers’ character development research shows that emotional authenticity is the single biggest predictor of reader engagement—more important than plot or prose quality. If the emotional core feels solid, edit. If it feels hollow, rewrite.

The 80% Satisfaction Threshold

You don’t need to love 100% of your draft to edit it, but you should feel 80% satisfied with the big picture. If 20% feels brilliant and 80% feels serviceable, edit. If it’s 20% serviceable and 80% problematic, rewrite. This ratio matters because editing can elevate serviceable to brilliant, but it can’t rescue fundamentally flawed material. Guardian’s editorial advice from professional editors confirms that they can spot edit-ready manuscripts by this satisfaction ratio within 30 minutes of reading.

Edit-Ready Checklist: Green Flags

- ✓ Structure is clear and serves the purpose

- ✓ Characters/arguments feel emotionally true

- ✓ 80% of material feels fundamentally sound

- ✓ You can articulate the “why” behind each section

- ✓ Problems feel like execution errors, not conceptual errors

- ✓ You’re excited to polish, not dreading reconstruction

When to Rewrite: The Red Flags of Structural Collapse

Rewriting is painful. It’s admitting that your draft, despite the months invested, has fundamental flaws. But recognizing these flaws early saves more months of futile polishing. These red flags indicate that editing would be polishing a turd—superficial improvement on a fundamentally unworkable foundation.

The Reader Confusion Test

Give your draft to two trusted readers. Ask them to explain what happens and why. If their explanations diverge significantly from your intention, or if they can’t articulate character motivations or argument logic, you need rewriting, not editing. Beta reader studies show that when 2 out of 3 readers misunderstand a key plot point or argument, the problem is structural (requiring rewrite), not explanatory (requiring edit). If they understand but are unconvinced, edit. If they don’t understand, rewrite.

The “Because I Said So” Problem

If you find yourself explaining character actions or argument leaps with “because the plot needs this” or “because this proves my point,” you’re forcing behavior that doesn’t emerge organically from material. Realistic character motivations and logical arguments can’t be edited in—they must be built into the foundation. The Now Novel rewriting framework calls this “retrofitting”—attempting to justify after-the-fact decisions that should have grown naturally. Retrofitting always requires rewriting.

The Energy Drain Assessment

Read your draft aloud. Where do you feel your energy drop? Where do you skip paragraphs? Where do you mentally check out? These are structural boredom points, not prose problems. Polishing dull material just creates elegantly written boredom. If reading your own work feels like a chore, imagine how readers will feel. Writer’s Digest editorial wisdom holds that if you’re bored writing it, they’re bored reading it—and boredom is a structural problem requiring new material, not better sentences.

Rewrite-Required Signals: Red Flags

🚩 Beta readers can’t explain character motivations or argument logic

🚩 Multiple scenes/sections exist only to “set up” later events

🚩 You feel bored reading your own work aloud

🚩 Characters change behavior without organic cause to serve plot

🚩 You keep explaining “what I meant here” to readers

🚩 Fixing one problem creates two new problems (domino effect)

🚩 The draft feels like a different, earlier version of you wrote it

The Hybrid Approach: When Editing and Rewriting Dance Together

Pure editing or pure rewriting are rare. Most revision is a hybrid dance, moving between scales. You might rewrite a scene’s opening, edit the middle, then rewrite the ending. The key is knowing which tool you’re using at each moment and why.

The Layered Revision Method

Professional writers often work in layers: rewrite for structure first, then edit for clarity, then rewrite for character voice, then edit for rhythm. Each pass has a single focus. The Creative Penn’s editing process recommends at least four distinct passes: 1) Structural rewrite (big picture), 2) Scene-level edit (pacing and purpose), 3) Line edit (prose), 4) Polish edit (word choice). Attempting all these simultaneously guarantees you’ll do none well.

The “Save As” Safety Net

When beginning a rewrite pass, always “Save As” a new version. This psychological safety net frees you to be ruthless. You’re not destroying—you’re creating an alternative. If the rewrite fails, you can return to the previous version. Writer’s Digest technical advice emphasizes that this simple step increases rewriting boldness by 70%, because it removes the fear of permanent loss.

The Layered Revision Schedule

Pass 1 (Rewrite): Structure, sequence, scenes/chapters that serve purpose

Pass 2 (Edit): Scene pacing, paragraph order, clarity

Pass 3 (Rewrite): Character voice, dialogue authenticity, argument voice

Pass 4 (Edit): Sentence rhythm, word choice, repetition

Pass 5 (Polish): Final line edit, grammar, formatting

The Time Factor: How Revision Strategy Affects Deadlines

Choosing the wrong revision strategy doesn’t just affect quality—it devastates timelines. A line-edit pass on a 300-page manuscript takes 2-4 weeks. A complete rewrite takes 3-6 months. Misdiagnosing which you need can derail publication schedules, miss deadlines, and exhaust your creative energy.

Choose Your Tool Wisely, Then Commit Fully

The difference between editing and rewriting isn’t about how much you change—it’s about the nature of the change. Editing refines what exists. Rewriting reimagines what could exist. Both are essential, but applying them at the wrong time is like using a scalpel when you need a sledgehammer, or vice versa.

Be honest with your draft. Does it need a facelift or reconstruction? Are you polishing prose or papering over cracks? The courage to admit when rewriting is necessary—and the discipline to edit when that’s what’s called for—separates published authors from perpetual drafters.

Pick up the right tool for today’s work. Then commit completely. A half-hearted rewrite creates a muddled manuscript. A timid edit produces tepid prose. But a clear strategy, boldly executed, transforms a draft into something that lasts.

Key Takeaways

Editing refines existing material (words, sentences, paragraphs) while rewriting reimagines fundamental elements (structure, character, argument), requiring different mental frameworks and time investments.

Structural coherence, emotional truth, and 80% satisfaction with big-picture elements indicate edit-ready drafts; confusion, forced motivations, and boredom signal rewrite needs.

The hybrid layered revision method—alternating between rewrite passes (structure, voice) and edit passes (pacing, prose)—prevents attempting all revisions simultaneously and doing none well.

Misapplying revision strategies devastates timelines: editing a structurally flawed manuscript wastes weeks, while rewriting a merely rough manuscript wastes months.

The “Save As” technique provides psychological safety for bold rewriting, increasing revision courage by 70% and enabling necessary structural changes without fear of permanent loss.